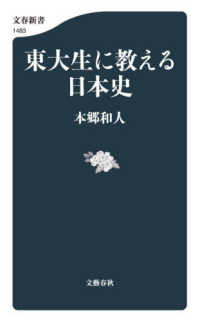

Full Description

In England, the horse chestnut or conker is a much-loved tree. Its edible cousin, the sweet chestnut, is valued here in winter for a turkey stuffing or a bag of hot nuts from the brazier, but is less common than in warmer southern climes where it has been an actual staple of the diet of some regions, as well as a crowning delicacy of sweet shops, patisseries and charcuteries. In fact, the horse chestnut is a relative newcomer, not arriving in Europe (from its home in northern India) until the 16th century. The sweet chestnut, originating in Asia Minor, has been with us since the earliest classical times. Both species have medical healing properties. The importance of the sweet chestnut to European diet has led to its being called l'arbre a pain by the southern French. Its high vitamin C content meant that it was once a popular cure for scurvy. Most importantly, it was a vital ingredient in Italian, French and Spanish cookery. Ria Loohuizen includes about 50 recipes for things as varied as a terrine of chestnuts and wild mushrooms, a breast of duck with chestnuts, pancakes made with chestnut flour, and the famous Italian chestnut cake castagnaccio. She also gives useful hints about roasting nuts on an open fire, choosing fresh nuts in the market-place, grinding chestnut flour, and making that best of all sweetmeats, marrons glaces.

Contents

Foreword by Jill Norman I The horse chestnut, Aesculus hippocastanum Growth and habitat Etymology Uses Recipes for the home dispensary II The sweet chestnut, Castanea sativa Growth and habitat Cultivation Uses History A Methuselah among chestnuts Food value Medicinal value Harvesting Storage Peeling Chestnut flour and dried chestnuts Roasting Chataigne or marron III Recipes for sweet chestnuts Weights and measures First courses Soups Chestnuts with vegetables Stuffings Fish, poultry and meat Bread, cakes and desserts with chestnut flour Bread, cakes and desserts with whole chestnuts Bibliography Acknowledgements Index